From Queen's Gambit to Beijing's Gambit

The Queen’s Gambit is a 7-episode miniseries released on Netflix in October this year. It is a fictional story that follows the life of an orphan chess prodigy, Beth Harmon, during her quest to become the world’s greatest chess player while struggling with emotional issues and drug and alcohol dependency.

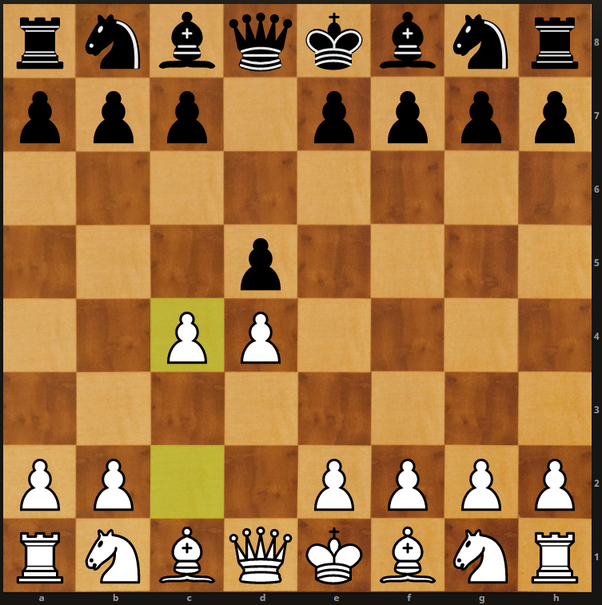

The word “gambit” refers to a kind of opening in which a player makes a sacrifice, typically of a pawn, for the sake of some compensating advantage. In other words, the player trades short-term benefits for long-term benefits. In the opening known as Queen’s Gambit, the White player sacrifices a pawn on the queen’s side.

The movie used this name as the title not only because this was the opening played in the final match of Beth but also because it stood for the sacrifice, explicit or implicit, our female protagonist made in her life.

Beth’s gambit

The gambit Beth has made in the movie can be grouped into two types, according to whether they are explicit or implicit.

The explicit gambit is quite clear. To boost her imagination and thus the ability to play chess in her head, Beth developed a dependency on drugs (known as tranquilizers). Later, Beth further developed an addiction to alcohol and tobacco upon the loss of chess games as well as her adoptive mother.

The implicit gambit is not that evident. It can be best observed in a conversation between Beth and her adoptive mother, wherein her mother told her that chess was not the only thing in life. Well, her mother might not be the model to learn from, but she was right in that Beth was not living her life but was merely a container of her chess talent. She sacrificed a normal life for the quest to beat every chess player in the world.

Beth’s talent

It is her talent that won Beth countless games and made her a regional champion.

Indeed she was hardworking, but she was not paying effort. What she did was just letting her talent exploit her, occupy her life, and crowd out other activities that a normal girl would enjoy. When she could not concentrate, she appealed to drugs. She was just a burning candle with her chess talent as the flame on top.

It is hard to say whether Beth enjoyed chess more or the glory associated with the wins more. They are combined. Beth was not that different from Pavlov’s dog.

No matter how Beth’s talent is great, there is a limit to which talent can bring her. The talent could make her a regional champion and a national co-champion but failed to make her an international champion. She eventual hit the wall known as Borgov, the number one chess player in the world.

For her, Borgov was not an opponent that she could surpass through her talent or intuition alone. No matter how hard she pushed on this wall, the wall just sent the force back to her. The wall itself stayed motionless.

A single tiny candle may light up a bedroom, but it cannot light up a vast lobby. Beth’s winning in the past has more or less been effortless. Now, however, Beth needs to start to pay effort by working on herself, on her weakness. It is only through overcoming one’s weakness and surpassing oneself that one can become a great man.

Gambit based on talent

Gambits are not limited to our protagonist. We can observe such things nearly everywhere.

Asian teenagers work their ass off by sacrificing their childhood for the sake of getting enrolled in a prestigious university, which will ensure them a bright future.

Western girls (and now also eastern girls), probably misled by fairy tales, sell themselves to successful older sugar daddy for the sake of living a rich, worry-free life.

Gambits are not limited to individuals; it also applies to the countries. Because of the industrial revolution, production significantly improved, but at the same time, the environment was damaged. Although at that time, people were unaware of the consequence, it was still a gambit, an unintentional and implicit one.

Many food and drugs were originally considered harmless at their debut, whereas they were later found the cause of many diseases. For example, in the movie, the tranquilizer was initially distributed to the children in the orphanage but later forbidden by the law. These are all cases of implicit gambit.

Beijing’s gambit

In the queen’s gambit opening, both sides initially are in equal positions, and the White player chooses to trade a pawn for some other advantage. Nevertheless, in real life, the gambit is often made by people in the inferior position: They make the gambit not to gain advantages but to be equal to those in the superior position, a situation they can never reach otherwise.

For the chess player, gambits are options. For most people, however, the gambit is a must or is regarded as a must. Beijing has this exact mindset.

Beijing has long held a competitive mentality toward the US ever since the founding of the People’s Republic of China. What every leader, from Mao to Xi, thinks every day is to “make China great again.” They want to be not only the emperor of China but also the emperor of the world.

In this regard, they are willing to make every gambit, among which human rights. For them, Chinese people are the cement of their wall, the ingredient of their glory, and the fuel of their dream. Chinese people are everything but human beings. For them, Chinese people are not the ends but the means, the means to checkmate the US.

Beijing’s talent

Beijing’s talent is, obviously, the so-called advantage of low human rights. Uninfluenced by the Enlightenment, Chinese people are unaware of the importance of human rights and are de facto slaves. Ironically, in the national anthem of China, Chinese people are depicted as being unwilling to be slaves.

With the advantage of low human rights, Beijing sacrificed the benefit of peasants and quickly made China an industrial country. Beijing then continued on this path and made China the world’s factory. Although China has a trade surplus against the US, which means that Chinese people are paying for the consumption of American families, 600 million Chinese (nearly half of the population) have a monthly disposable income of less than $140.

The advantage of low human rights has made China the second-largest economic entity in the world. At this point, China seems to hit a wall just like Beth did in the movie. China’s GDP growth starts to fall, and it falls rapidly. China might fall into the middle-income trap.

As talent failed to make Beth the No. 1 chess player in the world, the advantage of low human rights fails to make China the No. 1 country in the world.

Beth was confused and lost. So is Beijing.

Reaction to failure

There are typically two types of reaction in front of failure.

The first type is the escapist’s way, which is the one chosen by Beth. She indulged herself in alcohol and tobacco and no longer touched chess.

The second type is the aggressor’s way, which is chosen by Mike Tyson. In his fight with Evander Holyfield, knowing that he had no hope to win, he bit off Holyfield’s ear.

Beijing appears to take the aggressor’s way, also known as the wolf warrior’s way. It initiated the “one belt one road” colonial project, splurged in Africa, and intensified territory conflicts with the rest of the world. Beijing is like a trapped, panicked beast, growling, waving its claws, and throwing itself in every direction, desperately.

China: a young lion or an old dog?

In the movie, Beth finally became aware of her weakness and started to work on herself. Will Beijing be able to be aware of its weakness? Or will Beijing be shackled by its talent?

If Beijing insists in relying on its advantage of low human rights, Beijing is essential an old dog, and the future of China is doomed.

You can’t teach an old dog new tricks.

If Beijing becomes aware of its weakness and works on it, then China will have the hope to become a young lion, as called by Napoleon.